Article Highlights:

- Recent interest in the Paleo diet has sparked public interest in eating based upon hunter-gatherer evolution.

- Interest in the Paleo diet has led to the adoption of the more extreme, Ketogenic Diet.

- In turn, the Ketogenic diet renewed the public’s interest in fasting (intermittent fasting, alternate-day fasting, and time restricted feeding).

- We encourage some (but not all) principles of the Paleo diet, some forms of intermittent fasting, and time-restricted feeding be adopted by modern day man.

- In our opinion, the Ketogenic diet and Alternate Day Fasting (ADF) have no place in public health; we believe these diets are passing fads.

- In this review we address the things you should consider before trying intermittent fasting (IF) or time-restricted feeding (TRF).

- We explain why, more than ever, there is a need for the modern-day consumer to create his/her own “Nutrition Rules” to build sustainable dietary patterns.

Introduction: Fasting, defined as prolonged periods of abstaining from eating or drinking anything containing calories has been practiced for millennia to cleanse the mind, body, and spirit. Therapeutic fasting for weeks and months at a time became a popular treatment of obesity in the 1950’s and 60’s before falling out of favor. In recent years, fasting has regained public interest in the form of intermittent fasting (IF) and time-restricted feeding (TRF). Fasting comes in many forms (see Table 1) but one of the more popular modern-day applications of it is alternate-day fasting (ADF).

Table 1. Definitions of Different Types of Eating Patterns. Reference: Anton, SD; 2018 Obesity

In ADF, one alternates between eating one day and fasting the next, thereby eating 2 days-worth of calories in one day and eating zero calories the other. In time-restricted feeding, one consumes all of his/her calories within a pre-determined time period. For example, in 10-hour TRF if your first meal comes at 8am, you are allowed to eat what you want, when you want until a set time point, let’s say 6pm. Thereafter, you’re not allowed to eat or drink anything containing calories. There may be some health benefits to IF and TRF; however, before we get into those we would like to explain how IF and TRF entered the mainstream as a way of eating. In short, IF and TRF didn’t just spring up out of nowhere. In our opinion, they are the offspring of the Paleo diet.

The Rise of the Paleo Diet: Unless you’ve been living under a rock (pardon our pun), you’ve likely heard something about the Paleo diet. The Paleo diet first entered the medical literature in 1985 as part of Eaton & Konner’s New England Journal of Medicine article, Paleolithic Nutrition: A Consideration of Its Nature and Current Implications. The Paleo diet laid dormant in the medical field for ~15 years until the early 2000s when Colorado State professor, Loren Cordain published a series of articles on the Paleolithic way of eating. It wasn’t until recently (the past five years or so) that the Paleo diet truly entered mainstream America.

In short, the Paleo diet is based upon what our ancestors during the Paleolithic era (2 million years ago to 10,000 years ago) had access to. This time period was long before farming, agriculture, or caring for livestock. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors ate wild game and scavenged for berries, nuts, and seeds. There was no industrialized food production or dairy products and there certainly weren’t any (farmed) grains.

The modern-day Paleo diet and its advocates do a fantastic job of pointing out how crazy, how insane, our food environment has become. The amount of ultra-processed, refined carbohydrate in today’s food environment is just staggering and one of the Paleo diet’s principles is to cut these out completely. This, for the most part, is a good thing.

However, with that being said, we are not fans of the Paleo diet as it tends to be overly restrictive. Reducing carbohydrate consumption in our modern-day world is probably a good thing for most people (more on this later) but completely cutting out all whole grain products, beans, and dairy is, pardon us, but just plain stupid. For this reason, we love, love, love, when people say that they eat based on Paleo principles or Paleo(ish) indicating that they reserve the right to some flexibility in their diets but in general follow the Paleo principles.

Finally, it must be noted that a) eating for health and b) eating for weight loss aren’t necessarily the same thing. When one becomes so wrapped up into thinking about what our Paleolithic ancestors used to eat, we lose sight of what, for many is our primary goal: to lose weight. Weight loss is about energy balance. Less calories in than calories out = weight loss. Although nice, it is not absolutely necessary to eat healthy to lose weight. No matter how much window dressing you put on a diet, the reason it works is because it helps you induce a negative energy balance (see Table 2).

Table 2. How Named Diets Work for Weight Loss. Despite their differences in name and appearance, any weight loss diet that actually works does so by creating a caloric deficit (negative energy balance).

Paleo’s Not Extreme Enough: Ketogenic Here We Come: As crazy as it is to hear, for many people the Paleo diet just wasn’t extreme enough…so they moved on to the ketogenic diet. In layman’s terms, the ketogenic diet is like the most extreme version of the Atkins diet on steroids (high fat, near zero carbs). The ketogenic diet doesn’t just restrict carbohydrate (again, the grain haters), it eliminates them! A true ketogenic diet also greatly reduces protein intake because protein (gluconeogenic amino acids) can be broken down to produce glucose, which the ketogenic diet seeks to severely limit through eliminating dietary carbohydrates (side note of importance: even if you haven’t eaten food containing calories for several weeks, your body will fight to maintain blood glucose; without blood glucose, you will die).

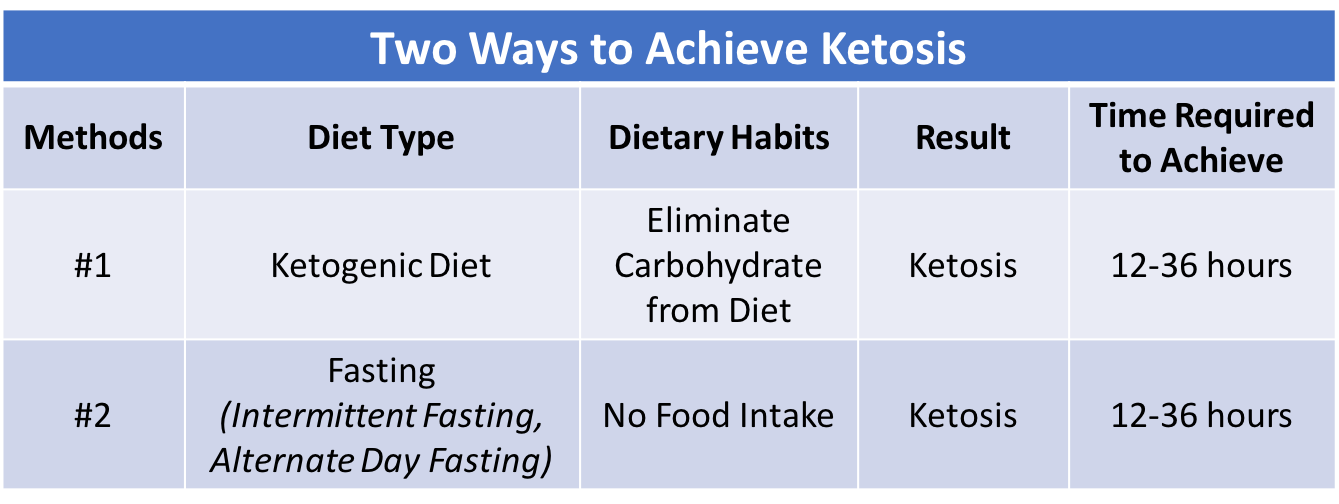

Table 3. There are Two Ways of Achieving Ketosis: eliminating carbohydrate from the diet or fasting. Each takes between 12-36 hours depending on your previous day’s diet and exercise.

By eliminating carbohydrates and/or fasting for prolonged periods of time, the body can enter a state of ketosis. Ketones (ketone bodies) are produced when there isn’t sufficient carbohydrate available to help the body burn fat. You can think of ketosis as

Evolutionary Underpinnings of the Hunter-Gatherer Diet: So why in the world would someone look to eliminate carbohydrate from their diets? Answer: in an attempt to mimic hunter-gatherer metabolism of the past. If we go back to the story of the hunter-gatherer, most people know that there were times of feasting when food was plentiful and fasting when food was scarce. Alternating between feasting (the fed condition) and fasting (fasting condition) leads the body’s metabolism to switch between glucose metabolism in the fed condition and fat metabolism in the fasted condition. Throughout our evolutionary past it was highly likely that our body’s metabolism had to remain highly flexible, that is, our metabolisms switched back and forth between glucose as our preferred fuel and fat as our preferred fuel, multiple times/day and hundreds, if not thousands of times per year.

Figure 1. Metabolic Flexibility. The body’s normal metabolism is highly flexible and responsive to carbohydrate intake. For the first two to three hours immediately after consuming carbohydrate, the body primarily burns glucose as a fuel. Thereafter the body switches to its backup fuel, fat, until another meal containing carbohydrate is consumed. Your body’s metabolism switches/flexes over to carbohydrate/glucose once again as carbs/glucose become the preferred fuel source. Only in starvation (2+ days without eating or total carbohydrate restriction (Table 3) does the body enter ketosis.

On the other hand, modern man never stops eating, therefore, modern day man never switches between glucose as a preferred fuel source or fat as a preferred fuel source (Figure 1). Forcing the body to switch between fuel sources seems to be good for metabolic health. Allowing the body to predominately use glucose and never have to switch between fuel sources is bad for metabolic health (heart disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, etc.).

As typical in our modern society of extremes, knowing that eating too many carbohydrates and/or eating too often can lead to energy excess and metabolic disease, people have swung the pendulum to the complete other side of the equation. This is completely unnecessary and carries no special “metabolic” benefit, but hey, that’s our society.

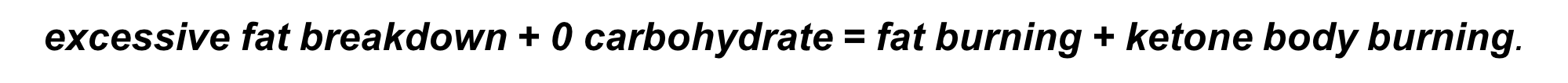

Before we move on, and in the interest of being balanced we would also like to state that it is possible to burn predominately carbohydrate (>70% calories) or predominately fat (>70% of calories) with limited metabolic switching and remain healthy. In his 2002, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition paper, Loren Cordain points out that our hunter-gather ancestors' diets were quite diverse depending upon geographic region and food availability. For example, in Table 3 you can see that the aboriginal Nunamiut of Alaska consume 99% of their calories from animal sources (protein and fat) compared to the Gwi of Africa, who consume upwards of 74% of their calories from plant sources (mostly carbohydrate). With all that being said, with the exception of the Nunamiut of Alaska and the Eskimos of Greenland, who live in far northern, short summer climates, the remainder of the aboriginal tribes likely exhibit metabolic flexibility as indicated by their diets.

Table 3. Proportions of Plant and Animal Food in Hunter-Gatherer Diets.

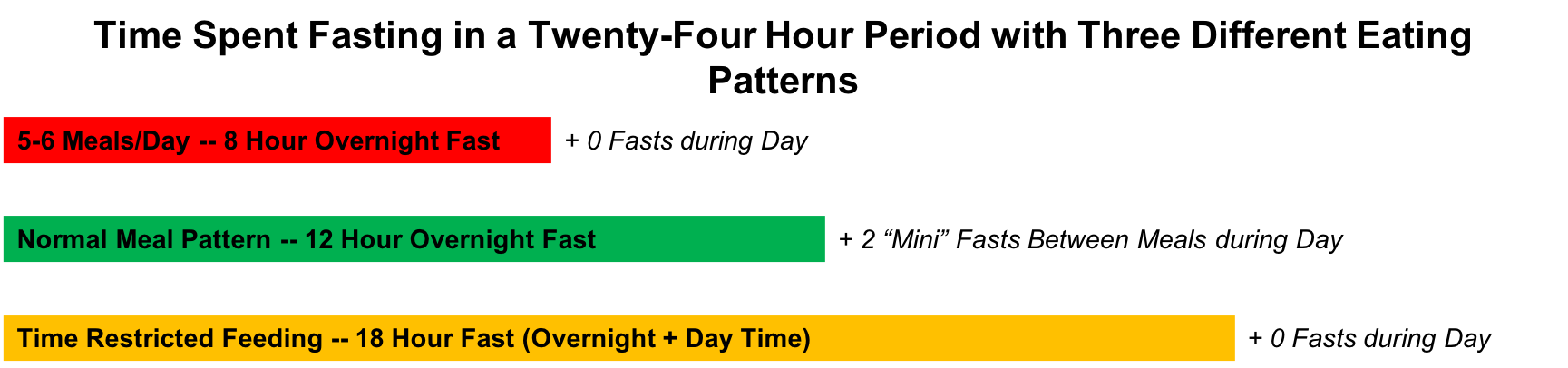

What Effect Does the Hunter-Gatherer Type Way of Eating Have on Modern Man? Unless you are eating every 3-4 hours, your body is going to alternate between glucose (fed condition) and fat (fasted condition) multiple times/day (Figure 1). If, on the other hand, someone is eating every 3-4 hours, it’s true, the body will never be forced to alternate between fuels (Figure 1. This is bad). Alternate-day fasting and time-restricted eating are just slightly greater extremes of what we already do (Figure 2, Normal Meal Pattern).

Alternate-day fasting and time restricted eating do make more sense than a ketogenic diet. In a ketogenic diet, your body is in a constant state of ketosis (Figure 1). In evolutionary parlance we have a term for this, it is called starvation. No ancestor in their right state of mind would voluntarily a) chose to go ketogenic and b) remain ketogenic when a food supply (carbohydrate) is available. People wishing to go ketogenic should stop messing around and go full on ketogenic like our ancestors during winter months when food is scarce and then eat normal during the spring, summer, and fall months. That would make much more evolutionary sense, but we digress.

We’ve Seen the Manipulation of Meal Timing Before: Intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding feel very much like a recent dietary fad manipulating the variable of meal timing and frequency. Do you all remember the advice to eat 5-6 small meals a day to keep your metabolism high? Well, there isn’t a shred of scientific evidence indicating 5-6 meals/day actually helps you lose weight over the long term. It feels to us that the health & wellness pendulum overshot eating at normal meal times (2-3 meals/day) and swung to the other extreme, eat 1-2 meals/day or zero meals on one day and an unspecified number the other day. This is really an individualized timing preference. If you are hungry eat just enough to appease your hunger and if you are not hungry then don’t eat. For the most part, it really is that simple. The trick again is more about calories in and calories out than timing or the number of meals per day.

Figure 2. The Effect of Feeding Patterns on the Number of Hours Spent Fasting During a 24-Hour Period. Prototypical eating patterns. The red bar represents frequent eating occasions (5-6/day) and 0 day-time fasting, the green bar represents a normal overnight fasting period of 12 hours and several day time fasting periods between meals (3) allowing for metabolic flexibility to occur, and the yellow bar represents time-restricted feeding and likely limited fasts during the day.

Energy Needs and Distribution are far Different in Modern Man versus Paleolithic Man: The IF and TRF dietary approaches don’t take into account the type of work many of us do, that is, intellectual deep thinking and critical analysis. This type of thinking takes a great deal of brain power and is exhaustive. The brain prefers to run on glucose so in a (prolonged) fasted state your brain may not be running on all cylinders (your brain can adapt to using ketones as its primary fuel but this takes time, during which you may be a little groggy). Although neither of us have tried these dietary approaches (for more than a day or two) and anecdotally, we’re positive that you can find people who swear that their energy doesn’t vary throughout the day or between fed and fasted days, this type of eating just doesn’t seem compatible with the type of work we do these days. Not to say that physical labor isn’t difficult. It sure as hell is difficult but it’s just different. You’re active, you’re doing. You have less time to think about how hungry you are or how you can’t concentrate. Our ancestors likely didn’t utilize the type of brain power we do on a daily basis and they certainly moved around a lot more than we do now as part of their hunting and gathering.

We Understand the Allure of Intermittent Fasting: We know that IF is lucrative because it contains only one set of rules. Time governs eating, nothing else. IF and TRF minimizes planning and the amount of time that you must dedicate to meal planning. You either eat or you don’t. This binary approach is very similar to other fad diets that eliminate or limit fat or carbohydrate by removing grains, gluten, beans, fruits, starchy vegetables, fatty meats, processed carbohydrates, and so on. These approaches are easy because they are so black and white, so simple. Yet, what do they all have in common? 1) They typically induce a negative energy balance, which leads to weight loss (Table 2) and 2) they typically fail after a few months. It is difficult to build consistency around black and white rules. Eating healthy is more nuanced than this. We have traveling, work lunches, happy hours, etc. These restrictive diets don’t allow for eating in all situations in life.

What should you do instead? We’re not going to give you the same old dietitian/health coach talking points of

- Drink eight, 8-ounce glasses of water/day

- Eat 5 fruits and veggies/day

- Eat 6-10 servings of whole grains

- Eat lean meats, mostly fish

- Eat nuts and legumes

Well, yes, we see the importance of these recommendations but we also recommend you

- Establish your own set of nutrition rules (however arbitrary they may seem).

- Take the time to find out what works for you by food logging/journaling.

- Build meals out of individual taste (and timing) preferences.

- Identify your obstacles to healthy eating and generate solutions to overcome them.

No one can tell you the answers to these questions but a health coach or dietitian can help guide you towards discovering these answers. Unfortunately, there is no healthy eating template. That’s what makes healthy eating so damn hard. If you don’t know where to start, start by logging your meals. You’ll quickly see what is and is not healthy. Then determine strategies to keep the healthy parts and improve the unhealthy parts. Nutrition is the easiest and the most complicated thing at the same time.

Who Shouldn’t do IF or TRF or Keto diets? We want to point out that a select group should not try these diets. If you have Type 1 or 2 Diabetes we would strongly discourage you from trying these diets (unless you are already well managed). Your goal is to maintain the balance between eating (glucose) and the insulin your body produces/you inject. Also some medications work best when taken with food. There are also a small set of studies that have looked at people with Thyroid issues. They too should be careful when on these diets as the main hormone, TSH requires glucose to be generated by the body. Without glucose available TSH is not made and therefore your metabolism will slow down causing further weight gain. People who are pregnant and children should probably also avoid these dietary practices. The best advice, if you have a pre-existing condition, please check with your Doctor or RD before making dietary changes.

Practical Implications: Like other dieting strategies, Intermittent Fasting (IF) and Time Restricted Feeding (TRF) are methods to induce a negative energy balance to lose weight. In our opinion these strategies represent extremes that are not feasible for the vast majority of individuals looking to either eat healthier or lose weight. However, less extreme versions of IF and TRF should be utilized to minimize unnecessary eating occasions. The practical implications of these interventions would include

- Eliminating Night Time Snacking

- Eliminating/Reducing Day Time Snacking

- Compressing Eating Hours to reduce calorie intake

Each of these strategies represent an opportunity to 1) reduce total caloric intake, 2) more fully establish your body’s natural rhythms that more closely represent our ancestral past, and 3) induce metabolic flexibility. Together, this represents metabolic health at its finest.

Todd Weber PhD, RD

Janel Schrader MS, MCHES