“How many calories do I need to eat to lose weight?” is a question I hear all too often. When people ask this question they are seeking a simple answer to a complex question, a question that cannot be answered with a one or two word statement. Unfortunately most nutritionists and personal trainers have been trained, both academically and culturally, to provide you with a simple answer.

Nutritionists will emphatically tell you the first you need to know to determine how many calories you should be eating is to first measure your basal metabolic rate (BMR). Your BMR is an estimate of the number of calories your body burns at rest and can be estimated using several well-accepted equations including the Harris Benedict and Mifflin - St. Jeor equations.

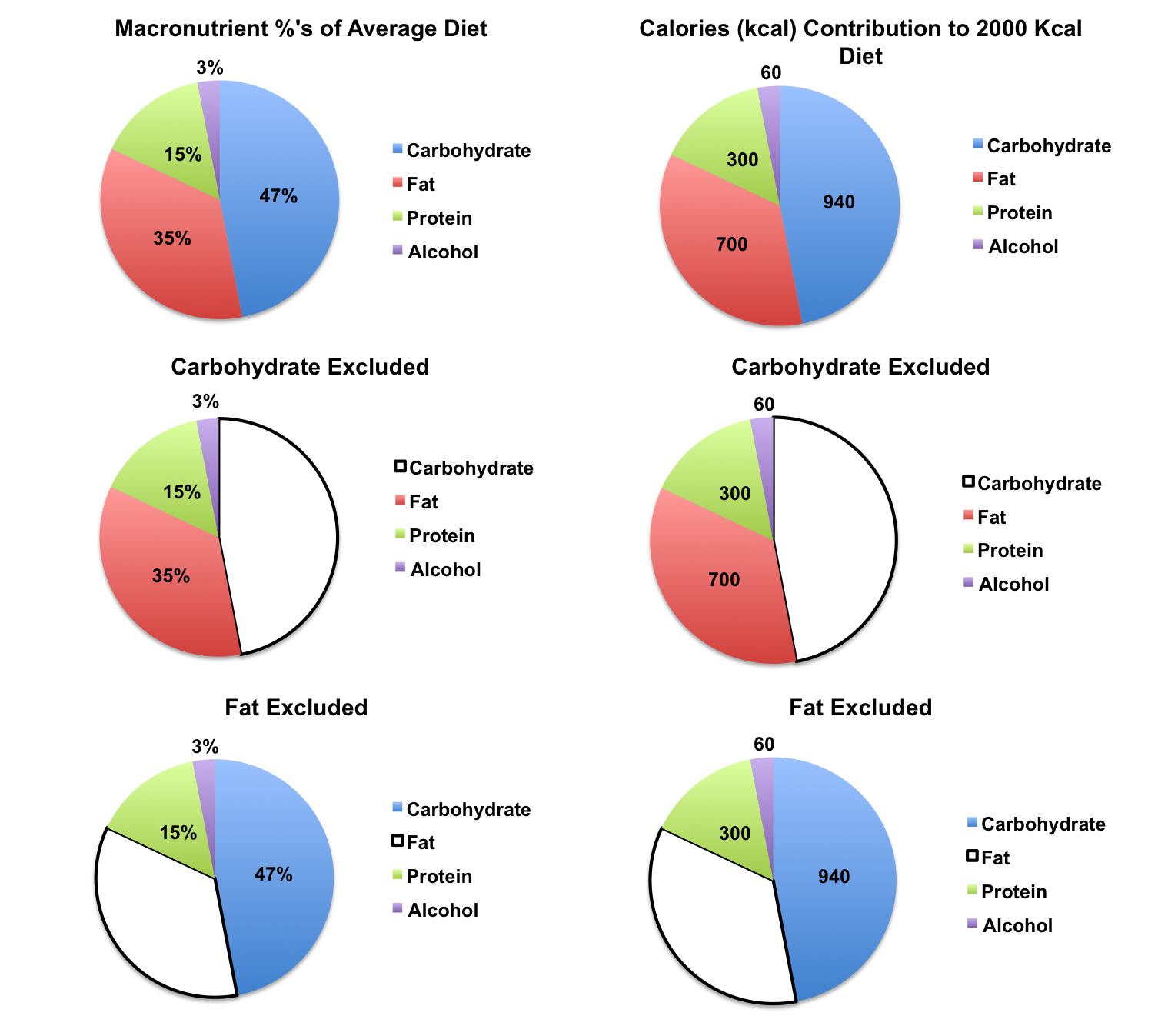

After calculating your BMR you will then be asked to multiply this number by an activity factor that helps account for the number calories burned during physical activity and/or activities of daily life. In doing so, you now have a number that represents an estimate of the total number of calories you burn per day. By knowing the number of calories you burn/day (let’s say it’s 2000 kcal) you can then estimate how many calories you need to eat to lose weight (<2000 kcal). This is BY FAR the most accepted method for prescribing the number of calories needed for losing weight. On the surface this method meets scientific standards, provides a quantifiable goal, and seems relatively easily to follow.

Calculating BMR and prescribing a diet from BMR is ideal in academic and research settings. However, this method fails miserably in the real world and I will show you why by providing an example of a theoretical person.

Jane Doe is a 45 year-old female who is 5’ 6’’ and weighs 200 pounds. Using the Harris-Benedict equation to calculate Jane’s BMR indicates her BMR is ~1630 kcal/day. The problem with this estimation is that BMR estimations may overestimate BMR in women by as much as 15% (1) . Therefore, her estimated BMR is 1630 kcal/day when in actuality her “real” BMR could be as low as 1385 kcal/day. This results in a difference of 245 kcals.

Next, let’s say that our Jane Doe multiples her BMR by an activity factor (to account for her daily exercise and/or movement) that she wants to do rather than what she currently does for physical activity. In this example we will say that our participant has moderate activity aspirations (factor 1.55) and is in actuality a mild activity exerciser (factor 1.375) (Here is the link to the activity factors). Based on the Harris Benedict equation and the estimated activity factor, it would be reasonable to come up with the following metabolic rates for Jane:

High Estimation of Physical Activity based on High Estimation of BMR: 1630 kcal/day x 1.55 = 2526 kcals/day

Real Estimation of Physical Activity based on High Estimation of BMR: 1630 kcal/day x 1.375 = 2241 kcals/day

Real Estimation of Current Physical Activity and Real Estimation of BMR: 1385 kcal/day x 1.375 = 1904 kcals/day

Jane’s nutritionist estimates that to maintain her body mass she needs 2526 kcal/day when in reality Jane may only require 1904 kcal/day. This is a staggering 622 calories more than what Jane likely needs to maintain her body weight! If Jane follows this prescription she will gain weight, not lose weight!

By now, it should be apparent that we are not great at estimating BMR to begin with, so it is difficult to prescribe a certain number of calories necessary to lose weight. To make matters worse, people are notoriously inaccurate when it comes to estimating food intake.

Estimated number of calories eaten versus the actual number of calories eaten. When obese individuals "think" they are consuming ~1900 calories they are actually consuming 2500 to 3000 calories (3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

It has recently been demonstrated that some individuals may underestimate the number of calories they consume in a day by as much as 800 calories or 41% of total daily calories (2). Other researchers have shown that obese individuals underestimate their calorie intake by 34% (3), 38% (4), 46% (5), 58% (6), and 59% (7) (see graph above). If we apply these figures to Jane Doe’s caloric needs of 1900 kcal, she would be underestimating her actual calorie intake by 646 to 1121 calories/day!

In a nutshell, we are the blind leading the blind. It is very difficult to accurately estimate our BMR or our physical activity, leading us, in some cases, to be off by as much as 800 to 1000 calories/day.

Now to be fair, if you are weighing and measuring your food and reading labels you will be able to come very close to the number of calories you set out to eat. If you are okay with weighing and measuring your every meal for the foreseeable future, then this method can work for you. But, are you really going to do that over the long term? Heck no! Weighing, measuring, and counting calories are a pain in the butt. No one outside of the extremely dedicated (think bodybuilders) can keep this type of practice up for months and years.

There is another popular method for measuring BMR that is used incorrectly that I will touch upon briefly. This method is known as indirect calorimetry and involves collecting the gases you expire from your mouth, funneling those gases through a tube to an analyzer in a metabolic cart, and calculating the number of calories you are burning based on principles of metabolism. The metabolic cart is a cornerstone of exercise physiology classes at academic institutions but it is used incorrectly in clinics and gyms to calculate BMR and here is why.

Due to time constraints and the fact that breathing through a mouthpiece into a hose is not very comfortable, indirect calorimetry tests to measure BMR typically last only 30 minutes. Most fitness type facilities offering BMR tests also do not have a room dedicated to measuring BMR. BMR should be measured in a dark, noiseless room while resting, but not sleeping, in a supine position. More often than not the BMR measured in the fitness facility is performed in a well-lit, shared room, with numerous noisy distractions. It is a gym what else would you expect! More than likely your estimate of BMR will really be an estimate of resting metabolic rate (RMR) due to the minor stress associated with the confounding factors of light, a shared room, and noisy distractions. In this situation, even saying that the RMR measurement will be accurate is a pretty big stretch. The estimate of BMR you get from this test will be higher than your actual BMR because it is not truly a resting test.

In addition, even if the conditions for measuring BMR are optimal, the majority of BMR tests are only performed for one hour with the last 30 minutes of data used to calculate your BMR. We then take these 30 minutes of data and extrapolate this number to cover a 24-hour period. This practice of extrapolating is very much flawed because you are using 30 minutes of resting metabolic data to determine the other 23.5 hours of someone’s life that involves activities of daily living, exercise, eating, and sleeping. With all these other confounding variables you are relying upon an estimate of an estimate to determine one’s caloric needs. If you are the type of person that just really HAS to know your BMR, I would recommend saving the $100 you’d drop on an indirect calorimetry test and use the Harris-Benedict or Mifflin St. Jeor equation instead.

The bottom line is

We are not good at estimating the number of calories we should be eating

We underestimate the calories we DO consume

We overestimate how many calories burned during physical activity

We really have no idea how many calories we eat or how much we move.

So What is the Solution? As I have pointed out in my Energy Balance webpage, let your bathroom scale guide you as to how many calories you should be consuming. If you’re gaining weight, you’re eating more calories than you burn. Losing weight, you’re burning more calories than you consume. If you’re weight stable, your calorie intake equals your calorie output. It sounds too simple but it really does work.

Calories In. Trying to estimate the number of calories you should be eating in a day and trying to count calories to match this number is not practical or sustainable.

Instead of micromanaging this process, cut down on portion sizes, decrease the number of meals and/or snacks/day, and choose light/reduced fat products to reduce the number of calories you consume. Take the time to carefully plan out your meals and snacks for the week by answering the questions provided in my grocery shopping webpage.

Calories Out. The number of calories burned during a workout can be estimated by the machine you are using to exercise (bike or treadmill) or it can also be measured with a heart rate monitor. Caloric expenditure estimates from bikes, treadmills, and ellipticals are based off mathematic equations, fail to consider the individual differences in the person using the machine (height, weight, fitness status, body type, etc) and tend to overestimate the number of calories burned. Heart rate monitors are fairly effective at measuring energy expenditure during a workout but what about the rest of your day? What if you don’t exercise in a gym? The heart rate monitor is pretty effective, but it is just not feasible to wear a heart rate monitor all day long. Besides, the battery will run out.

To gain a better understanding of how much you’re moving throughout the day (workouts and activities of daily living) I recommend utilizing an accelerometer (or what you usually hear called an activity monitor). Accelerometers are tiny devices worn on either your wrist or waistband that literally measure the speed of your movement (your acceleration) through space (hence the name accelerometer). There are seemingly hundreds of accelerometers out there, each containing slightly different features.

One of the more accurate, easy to use, and less expensive accelerometers is the Fitbit Zip. It is worn on your waistband and is barely noticeable to you or anyone else. Fortunately or unfortunately, the Fitbit does not lie. If I haven’t had a very active day, it tells me. It helps me to stay accountable to my exercise routine, whether that means getting to the gym or walking in the park. It will let me know that I have been active or need to move around a little bit more.

If you are interested in learning more about how active (or inactive) you are or want some more accountability in your physical activity routine, click on the Fitbit link and it will take you to Fitbit’s webpage where you can get one for yourself. One final thing I like about the Fitbit is that it is downloadable. You don’t have to manually track your exercise. Just place it next to your computer docile (which comes with the purchase of a Fitbit) and voila, the data is downloaded to your computer!

Is estimating basal metabolic rate and counting calories really worth it? Hopefully I have convinced you it isn’t necessary. Instead of estimating metabolic rate and counting calories; meal plan, grocery shop, let your scale guide you, and monitor your daily physical activity. By following these simple steps you’ll be well on your way to a healthier, happier life without all the hassles, time, and expense of estimating BMR and counting calories!

For more of my thoughts on estimating metabolic rate and counting calories, please see: Counting Calories: a Short-Term Solution to a Long-Term Problem.

References:

McMurray RG, Soares J, Caspersen CJ, McCurdy T. Examining variations of resting metabolic rate of adults: a public health perspective. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. Jul 2014;46(7):1352-1358.

Archer E, Hand GA, Blair SN. Validity of U.S. nutritional surveillance:National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey caloric energy intake data, 1971-2010. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e76632.

Prentice AM, Black AE, Coward WA, et al. High levels of energy expenditure in obese women. British medical journal. Apr 12 1986;292(6526):983-987.

Goris AH, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Westerterp KR. Undereating and underrecording of habitual food intake in obese men: selective underreporting of fat intake. The American journal of clinical nutrition. Jan 2000;71(1):130-134.

Platte P, Pirke KM, Wade SE, Trimborn P, Fichter MM. Physical activity, total energy expenditure, and food intake in grossly obese and normal weight women. The International journal of eating disorders. Jan 1995;17(1):51-57.

Buhl KM, Gallagher D, Hoy K, Matthews DE, Heymsfield SB. Unexplained disturbance in body weight regulation: diagnostic outcome assessed by doubly labeled water and body composition analyses in obese patients reporting low energy intakes. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. Dec 1995;95(12):1393-1400; quiz 1401-1392.

Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. The New England journal of medicine. Dec 31 1992;327(27):1893-1898.